There are two main bits of “Magic” behind Time Machine, explained below:

- The File System Event Store — How changes are found quickly (blue box)

- Hard Links — How “incremental” backups are, in effect, full backups (tan box)

And some other, more technical, stuff, on separate pages:

- Backup Structure

- How Local Backups are Stored

- How Network Backups are Stored in Sparse Bundles

- Inclusion and Exclusion handling and the Preferences file

The File System Event Store is a hidden log that OSX keeps on each HFS+ formatted disk/partition of changes made to the data on it. It doesn’t list every file that’s changed, but each directory (folder) that’s had anything changed inside it. That saves lots of space in the log, since often there are multiple changes to the same folder. Each such change is called an event.

Any process can use it to find what’s been changed since the last event that process handled. That’s how Spotlight, for example, knows when a file has been added or changed and needs to be re-indexed.

Normally, Time Machine can use it to find out what’s changed and needs to be backed-up, since it’s far faster than comparing everything on your system to the backups, as some other backup apps do. (And it’s the reason that Time Machine can’t back up disks with other formats.)

But OSX can’t keep the log forever, of course, so if you haven’t done a backup in a long time, or there’s been a very large volume of changes (such as installing an OSX upgrade, which will add or change tens of thousands of files), the database won’t be complete. Or, if your system shuts down abnormally, such as from a software problem, power loss, or forced power-off, it will also be suspect. OSX will replace the Event Store and assign a new “UUID” to it (and send a message to that effect to your logs).

When that happens, the next backup will log a message about an “Event store UUID” not matching, meaning it’s not the same one as on the previous backup. Then Time Machine has to do a “deep scan” (“deep traversal” on Snow Leopard or Leopard), comparing everything on your system to the backups. If you see a long “Preparing” phase (“Calculating changes” on Snow Leopard), that’s what’s going on. From 10.6.3 through 10.6.8, you’ll see Scanning nnnn files messages on the TM Preferences Window and the TM Menu display from your menubar.

The time required for this depends on a number of things, but mainly the number of files on your system (more than the total size), and the type of connection to your backups. So a relatively small system using a FireWire800 external drive will be far faster than a larger system being backed-up wirelessly to a Time Capsule.

Hard Links act a bit like aliases, but much more efficiently, and are the key to how Time Machine can back up only what’s changed, but have each backup be, in effect, a full backup of everything that was on your system at the time.

When Time makes your first backup, it copies everything (except some system work files, trash, etc). It also makes a dated backup folder, and places hard links in it to all the backup copies it just made. Then when Time Machine makes a second backup, it copies everything that changed since the first backup, makes another dated backup folder, and puts hard links in it to the new backup items. So far, so good.

But here’s the trick: it also puts hard links in the second backup folder to the items that didn’t change. So the folder now contains links to everything that was on your system at the time of the second backup.

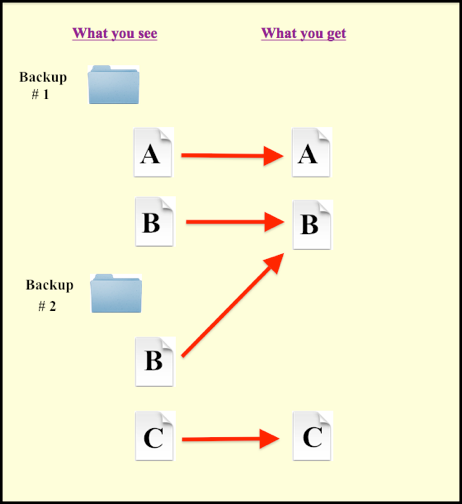

This is greatly oversimplified, but should illustrate how it works:

- Create File A and File B, and run an initial backup (backup folder #1 below).

- Then delete File A, create file C, and run another (backup folder #2 below).

- If you look at the backup folders via the Finder, you’ll see a bit of an illusion:

It appears there are two copies of File B, but there aren’t; each Backup Folder contains a hard link to a single copy of File B.

This also explains how, when it’s out of space, Time Machine can delete your first backup, but all the other backups are still full versions of your system: the trick is, the backup folder and all its hard links are deleted, but the actual backup copies aren’t deleted if there are any remaining hard links to them. If Backup Folder #1 is deleted, the backup copies of files B and C remain (and you regain only the space used by File A on your backup drive).

A little “twist” to this is, if you add-up the sizes of the two Backup Folders, you’ll count File B twice! This is because, unlike a “normal” file system, the backup copies don’t “belong” to one particular backup folder — they’re in both folders at the same time. That’s why you’ll get odd figures from the Finder and/or 3rd-party utilities — sometimes the Backups.backupdb folder is much less than the total of the backup folders; other times it will be shown as the sum of them, possibly much larger than the backup drive!

Now you’re probably thinking, there must be about a zillion of those hard link thingies in every backup folder, taking forever to create and delete. But Time Machine has yet another trick up it’s sleeve: If nothing in a folder is changed, Time Machine makes a single hard link for the folder, not one for each file inside it. This is especially slick when you think about your system folders: they contain tens of thousands of folders and sub-folders several levels deep, that rarely change. So instead of making a couple of hundred thousand links for every backup, there are often only a few.

In fact, the OSX File System was changed effective with Leopard to allow these “directory-level” hard links, so Time Machine would work. That’s one of the reasons why Tiger and earlier versions of OSX (not to mention other operating systems) are mystified by Time Machine backups. They cannot make any sense of the links that look like folders.

-- EOF --除非注明(如“转载”、“[zz]”等),本博文章皆为原创内容,转载时请注明: 「转载自程序员的信仰©」

本文链接地址:How Time Machine Works its Magic [zz]

Today on history:

【2012】张小龙谈移动互联网产品设计原则 [zz]

发表回复